By Chris Mhike

That Zimbabwe’s media law and policy framework is seriously flawed and therefore in dire need of improvement has been palpable for a long time now.

In recent years, the executive, legislative and judicial branches of Zimbabwe’s government, have all repeatedly acknowledged the need for legislative and policy reforms in the media sector.

The Fourth Estate, that is the press or the news media, have naturally been the most vocal in the call for media reforms. These calls grew louder than ever before in 2018.

Of course, it is the press and media freedom advocates whose cries and pleas for media reforms are sharpest. The harsh effects of defective laws and policies hit media workers the hardest.

As we fold 2018 and get ready for 2019, the media reform story this year, has been one of a government that has been blowing hot, blowing cold. A person who blows hot and cold is one who sometimes seems enthusiastic or interested about something, and at other times does not.

The year generally started on a hopeful note for many long-suffering Zimbabweans who hoped the newly installed government would pull the nation out of the economic morass that had ravaged millions of families in recent years.

In the fresh aftermath of the fall of former President Robert Mugabe, the media also hoped for better days because, by the time of the coup that ejected him from office, Mugabe had for long been widely considered to be an enemy of press freedom.

On World Press Freedom Day in May 2010 Mugabe was identified by Reporters Without Borders to be one of 40 “predators of press freedom” … an inglorious list of politicians, government officials, religious leaders, militias and criminal organisations that grossly undermined media freedom around the world.

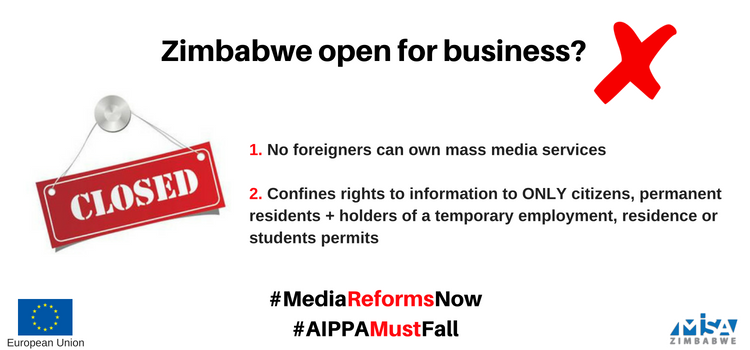

The post-Mugabe administration identified itself as a “new dispensation” whose ways would be different from Mugabe’s. “Zimbabwe is open for business”, became the new mantra that became the basis for a nation’s hope for tangible regeneration, including meaningful media reforms.

The new government led by President Emmerson Mnangagwa promised from the outset, that is at the end of 2017, that it would be guided by democratic principles and would, therefore, repeal bad statutes, promulgate progressive laws, liberalise the airwaves, and align all laws and policies (specifically including those that relate to the media) with the Constitution.

In 2018, the Ministry of Information, Publicity and Broadcasting Services (led by Minister Monica Mutsvangwa, Deputy Minister Energy Mutodi, Permanent Secretary in that Ministry – Nick Mangwana, as well as other Ministry officials), worked very hard in advancing the media reform agenda.

They commendably intensified the engagement process by meeting with owners and senior journalists from major media houses. They participated at the Media Alliance of Zimbabwe’s (MAZ) All Media Stakeholders Conference, at Multi-Stakeholder consultative workshops on the realignment of media laws in Zimbabwe, and at Round-Table consultations on media reform.

On his part, as he opened the First Session of the Ninth Parliament of Zimbabwe in September 2018, President Mnangagwa included the media reform theme on government’s legislative agenda.

“In line with our determination to further open up our media space, the Bill for the establishment of a Zimbabwe Media Commission, and an Amendment of the Broadcasting Services Act, shall be tabled,” said the President.

This year, promises were also made by government officials and by Parliament to the effect that the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA), would either be repealed or extensively amended.

Also up for review would be the Broadcasting Services Act, cyber laws, and the Zimbabwe Media Commission (ZMC) Bill. These have been positive and hope-inspiring developments that could be seen as a sign of better times for the media in 2019 and beyond.

These, and other progressive movements in 2018, perhaps invoke an image of a government that is hot about the media reform agenda.

Regrettably, 2018 also turned out to be a horribly cold year for too many journalists and media workers.

Herewith some of the illustrative incidents.

In May 2018, senior reporter Blessed Mhlanga was assaulted by then Deputy Finance Minister and Member of Parliament, Terrence Mukupe, during a live broadcast programme at Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation’s Pockets Hill studios.

On 3 August 2018, just after the general elections, journalist Tinotenda Samukange, was detained for close to three hours by soldiers who had been deployed for an unclear post-election operation in Kuwadzana, Harare.

In July 2018, shortly before the elections, Zimbabwe Defence Forces’ (ZDF) director of public relations, Colonel Overson Mugwisi, singled out reporters Richard Chidza, Snodia Mawupeni and Blessing Mashaya for “bad and mischievous reporting”.

Renowned civil society leader, Siphosami Malunga, was also lumped together with these journalists as a ‘bad and mischievous reporter during the same ZDF’s press conference after the publication of his opinion pieces that were deemed to be too critical of the military.

At the end of September 2018, freelance journalist Conrad Gweru was arrested at an accident scene for “unlawfully and intentionally engaging in disorderly conduct by taking pictures and shouting at ZRP officers” following an accident involving a commuter omnibus. He was released only after being admitted to bail at court.

These arrests and threats have certainly had a chilling effect on journalism in Zimbabwe. Blowing cold!

Even more chilling signals came from the Information Ministry early in December 2018.

During a plenary session at a multi-stakeholder consultative workshop in Harare, Permanent Secretary Nick Mangwana intimated that the Broadcasting Authority of Zimbabwe (BAZ), would soon license 10 state-owned “community radio stations,” and that government had already set aside financial resources for the stations.

Government’s unhealthy determination to maintain a firm grip on broadcasting is extremely worrying and does little to inspire optimism in prospects for media reform.

Equally bothersome, is the government’s recent pronouncements regarding the impending merger of BAZ and the Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (POTRAZ); the content of cybersecurity laws, the restrictive nature of the ZMC’s regulatory powers, restrictions on foreign investment in the media, and the Ministry’s deafening silence on content generation laws and policies.

While great strides were made in 2018 by the government, media houses, civil society, journalists and media workers in building consensus on action points regarding media reform and in entrenching mutual confidence, it is vitally important at this critical stage of the reform process, for the executive and the legislature to recommit to key principles of healthy legislative and reform processes.

These principles include:

- sincere consultation

- securing the consent of the governed,

- following the Policy to the Bill to Statute format, (bearing in mind the reality that good policies yield good laws)

- respect for supremacy of the Constitution

- respect for regional and international standards.

Zimbabweans pray and hope for the normalisation of life, improvement in the quality of life, and restoration of good governance in 2019.

In the same breath, the media anticipates a shift from the current ‘hot and cold trajectory’ to a ‘hot, hot and hot’ course that will transform Zimbabwe’s media terrain from the current restrictive configuration to a truly free media that is envisaged under Section 61 of the Constitution.

End

________________________________________________________

The author is a Harare-based media lawyer. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect MISA Zimbabwe ’s official position/s on the subject matter.