By Jacqueline Chikakano

The coming into force of the Constitution of Zimbabwe (Amendment No. 20) Act in 2013 and with it, the introduction of various new provisions and rights necessitates the revision of obtaining laws.

In some instances, this also necessitates the introduction of new ones in a bid to ensure conformity of laws with the Constitution as well as its full implementation.

A number of views have been proffered regarding the progress of this alignment process but of note, is that media laws, broadcasting laws included, are part of the laws that the alignment project is currently focussing on as repeatedly emphasised by the Minister of Information, Publicity and Broadcasting Services since taking up that office.

To date, this Ministry has held consultation stakeholder meetings between the 26th and the 30th of November as well as between the 7th and the 8th of December 2018. These meetings were aimed at soliciting input on the extent to which media laws, the Broadcasting Services Act [BSA] included, need to be reviewed to align them with the Constitution.

Regarding the Broadcasting Services Act, a number of issues have so far been raised by a wide range of stakeholders regarding the alignment of this law. These issues, for example, relate to the licencing procedure, particularly the call for licence applications by the Broadcasting Authority of Zimbabwe [BAZ], the non-licensing of community radios to date, and the impact of technology and convergence on the licence classifications.

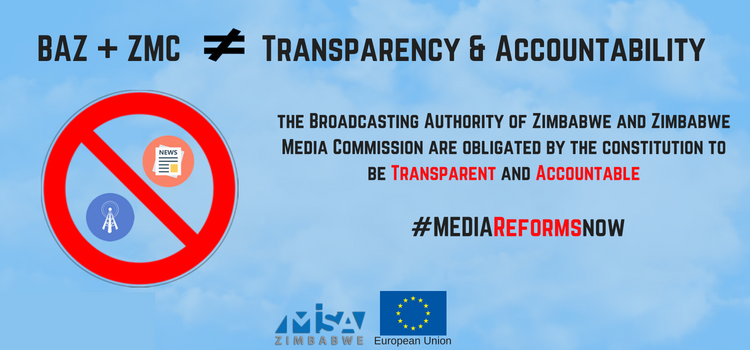

Another issue raised by stakeholders relates to the conformity of the current appointment process for the BAZ board with constitutional provisions on transparency, accountability and good governance as well as the need for a definitive permissible foreign investment/ ownership quota in the broadcasting sector, among others.

As the alignment process of the BSA progresses, it is worth reflecting on the scope and impact of some alignment issues raised to date as well as some non-alignment, but critical aspects that have an impact on this sector.

Licencing

Over the years, the delay by BAZ in calling for broadcasting licence applications following the coming into force of the BSA remains a major concern particularly in respect of community broadcasting.

Although in the past few years some classes of licences have been called for and issued, these have largely been commercial as well as content distribution service licences.

This obtaining situation has been attributed to the too wide discretionary powers that are vested in the BAZ in deciding when to call for licence applications and the lack of legal measures within the BSA to compel BAZ to make the calls.

This licensing framework which finds support in Section 10 of the BSA, is argued to be contrary to the freedom of establishment of broadcasters as provided for in Section 61(3) of the Constitution.

It is further argued that while the obtaining framework may not be unique to Zimbabwe, the fact that it has at the end of the day, curtailed the said freedom of the media and for broadcasters to establish themselves, calls for new legislative measures that clearly facilitate the enjoyment of these rights.

Proposals for periodic calls for licenses remains a major proposal for consideration. Ultimately though, the opportunity to align Section 10 of the BSA with the Constitution, should be looked at from a point of view of what measures work best within the Zimbabwean context towards fulfilling the rights in Section 61 of the Constitution and not necessarily being tied down to what others have done.

While the re-configuration of the licence call procedure is critical, the full realisation of the freedom to establish is also dependant on other issues which may have not been loudly debated to date. These include the constitution of the BAZ board, the absence of which according to the parent Ministry’s Permanent Secretary, Mr Nick Mangwana, [during his interview on STAR FM’s The Minister’s Desk, on the 17th of December], has halted progress regarding licensing of new players as there is no one to consider any applications at the moment even if they were called for.

According to the permanent secretary, the Ministry is currently working on ensuring that the BAZ Board is appointed and in place as soon as is possible and it can only be hoped that this materialises soon.

Licensing of community radios

During the recently held 7-8 December Stakeholder Consultation on the alignment of media laws with the Constitution, Permanent Secretary Nick Mangwana shared on the intention to have about 10 community radios licenced in 2019.

One topical issue though during that consultation was on the definition of a community for purposes of licensing community radios. As stakeholders wait in anticipation of this eventuality, some key benchmarks regarding community broadcasting are worth noting going forward regarding, particularly, the concept of a community and the envisaged “ownership” and purpose of such broadcasting entities.

The African Charter on Broadcasting [ACB] is insightful on this, defining community broadcasting as:

Broadcasting which is for, by and about the community, whose ownership and management is representative of the community, which pursues a social development agenda, and which is non-profit.

From this definition, it is clear that community broadcasting ought to be owned and driven by a specified community and this configuration is important as the review of the Act is done. Further, the ACB also provides that:

There should be a clear recognition, including by the international community, of the difference between decentralised public broadcasting and community broadcasting.

And from this, it is worth noting that whenever ‘community broadcasters” are licensed, these entities should conform to the envisaged characteristics of community broadcasters to avoid subsuming them under other classes of broadcasting or configuring them in a manner that strips them of the much-needed community identity characteristic.

Foreign investment in the broadcasting sector

Another emerging aspect from the stakeholder consultation workshops was on the need for foreign investment in the broadcasting sector as one of the measures to promote freedom of establishment of broadcasters.

To this call, the permanent secretary conceded that the issue needs to be re-visited, suggesting a permissible threshold of not more than 20% foreign investment. This proposal if passed, would also to some extent, be in line with the spirit of the Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment Act [Chapter 14:33] which also sets a permissible threshold for foreign ownership, although the quotas would be different.

This would also be in line with standards in other jurisdictions where a specified permissible quota is outlined in the laws. In South Africa, for example, Section 64 (1) (b) of the Electronic Communication Act, permits foreign investment in commercial broadcasting licensees for up to 20% while the Namibian Communications Act [2009] reserves 51% shareholding to Namibian citizens.

Converged broadcasting and telecommunications regulation

In April 2018, the then permanent secretary in the Ministry of Media, Information and Broadcasting Services (George Charamba), announced that Cabinet had made a decision to merge the broadcasting regulator, BAZ, which is established in terms of Section 4 of the Broadcasting Services Act [Chapter 12:06] with the Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe [POTRAZ], which is established in terms of Section 3 of the Postal and Telecommunications Act [Chapter 12:05].

The proposed merger was also discussed during the recent Ministry of Information’s stakeholder consultation workshops during which the current permanent secretary of information expressed hope that this would be dealt with legislatively during the ongoing process to align the BSA.

The proposed converged regulatory framework is an approach that has been taken by other countries within and beyond the region. In South Africa for example, the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa [ICASA], was formed to replace the Independent Broadcasting Authority and the South African Telecommunications Regulatory Authority.

In that regard, a separate Act, the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa Act [No. 13 of 2000] was passed to provide the operational framework for this converged regulator.

Namibia’s Communications Act [No. 8/2009], also establishes the Independent Communications Regulatory Authority as a converged regulator to, among other things, regulate telecommunications services and networks, broadcasting, postal services and the use and allocation of radio spectrum.

The Kenya Information and Communications Act [Chapter411a], also establishes a converged regulator in the form of the Communications Commission. Beyond the region, the UK converged the radio communications and the broadcasting and telecommunications sector into one regulator, the Office of Communications [OFCOM] in 2003.

Australia in 2005, also formed the converged Australian Communications and Media Authority [ACMA].

While legislative and other mechanisms towards the realisation of this merger are underway, a number of aspects will require further thought.

For example, on the impact of this (proposed) merger on each of the currently separate entities in terms of roles, responsibilities and the operational legal framework. On the latter, more thought is required on whether a new law is required to establish the converged regulator or whether this can be effected through just amendments of existing laws.

The common trend, however, is the passing of a separate enabling law that formally establishes the converged regulator, accompanied by subsequent amendments to both the Broadcasting Services Act or the Postal and Telecommunications Act’s provisions relating to the two regulatory authorities.

Other issues for further consideration include funding. for example on how the separate funds that both BAZ [The Broadcasting Fund] and POTRAZ [The Universal Services Fund] hold for different sector-specific reasons will be handled and applied under a merged framework.

Another key issue that the converged regulator would have to deal with, is the need for mechanisms aimed at curtailing monopolies in either sector. The licensing framework, in particular, will also have to be framed in a manner that is alive to competition issues.

More-so, at a time where convergence has seemingly placed telecommunications companies, and from another angle, over the top media services [such as Netflix and Youtube, at an advantage over mainstream broadcasting services.

Another major issue for consideration in respect of the converged regulatory framework, is also in terms of which ministry the converged authority will fall under as currently, the two [BAZ and POTRAZ] are under different Ministries.

In South Africa at the moment, both mandates currently fall under one entity i.e. the Department of Telecommunications and Postal Services.

Impact of over the top services on broadcasting services and regulation

While measures are being taken to align the BSA with the Constitution, one emerging issue that may need to be borne in mind, is the expansion and impact of Over the Top media services [OTTs] on the viability of traditional broadcasting services.

There is a debate on the extent to which such services should be regulated with countries employing different approaches.

One major issue though has been on the need for approaches that ultimately maintains a balance on competing for commercial interests as well as the digital and other rights of the users. Caution on this would need to be employed even in the Zimbabwean context as well.

In a manner of speaking, OTTs are content provision services that distribute media content directly to viewers via the internet and in the context of broadcasting, this is done without use or need for broadcasting frequency spectrum.

Complaints regarding OTT services have, among others, centred on unfair competition from OTTs that are not subject to the same regulatory obligations as network operators and traditional broadcasting services. Resultantly, there is a growing lack of a level playing field at the expense of traditional content providers such as broadcasters.

If the broadcasting industry is to continue viably, BAZ and POTRAZ or the envisaged converged regulator and indeed the government may need to reflect more on what measures need to be put in place to strike a balance between OTT services and traditional broadcasting services.

That is, in terms of ensuring that traditional media is not overly burdened with costs of doing business and other limiting regulatory requirements that put them at a further disadvantage with OTT services which do not face such and which are largely unregulated.

Measures could include a licensing framework that promotes traditional broadcast media to remain competitive.

As debates around OTT services continue, what is emerging clearly is that the challenges relating to OTT services are cross-cutting, affecting both conventional broadcasting media as well and the telecommunications and internet governance framework at large.

It thus requires a collective response from all affected sectors and would also be best if implemented by a converged regulator, among other measures.

Conclusion

While the alignment of the BSA with the Constitution is most welcome and greatly anticipated, it should be borne in mind that while this will result in great strides in the realisation of various rights and the growth of the broadcasting sector, more will still need to be done beyond alignment and towards a broadcasting framework that is both current and futuristic in line with the rapid changes in technology.

The writer, Jacqueline Chikakano is a lawyer and legal researcher with an interest in media law and policy issues. This article was commissioned by MISA Zimbabwe, as is part of its campaign on the realignment of media laws with the constitution of Zimbabwe.