By Admire Mare

IT’S almost two decades since Zimbabwe promulgated one of the most draconian pieces of legislation, which has impeded the growth of professional and citizen journalism and also hamstrung operations of private and international media organizations.

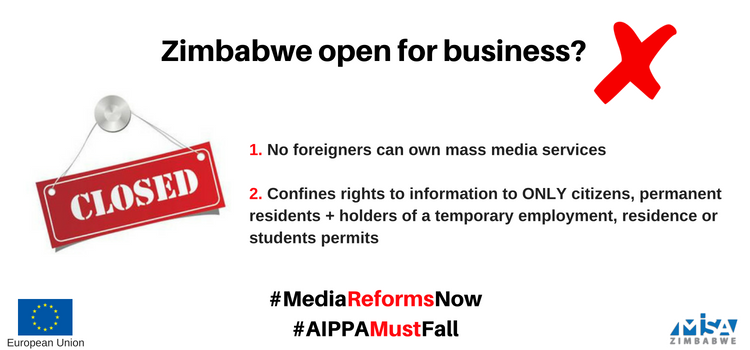

Despite the enactment of the 2013 Constitution that provides for explicit guarantees for the right to information and an enactment of a law that would ensure the enjoyment of the same, AIPPA remains part of the country’s statutes without fully promoting or guaranteeing the right to information as envisaged in the constitution.

This further contradicts statements by President Emmerson Mnangagwa that the ‘past is dead’. In fact, the past is still alive and the remnants of the ‘ancient regime’ continue to cause a chilling effect on the practice of both citizen and professional journalism.

AIPPA which was passed on the 22nd of March 2002 seeks amongst other issues to regulate the right of access to information; the right to request correction of personal information; data protection; protection of personal privacy and regulation of mass media.

It is clear from the above that the Act attempts to chew more than it can digest by regulating both data protection (which is very much an issue requiring a legislation which has inbuilt necessary and proportionate principles) and operations of mass media (yet we are already talking of converged media environment).

By regulating the media and establishing the Zimbabwe Media Commission (ZMC), the Act does not only entrench statutory media regulation but also cements the impression that access to information is a media rights issue.

The two are different and as various instruments on access to information espouse, while media do benefit from a democratic access to information regime, the right is ultimately about citizens being empowered with information that they can use to participate on matters important to their lives from an informed position as well as hold those in office accountable.

The Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No. 20) Act of 2013 [the Constitution], provides for a number of rights that fall within the regulatory focus of the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act [AIPPA].

Besides the 2013 Constitution, there are many regional and international standards on aspects such as regulation of the media and on promotion and protection of access to information which further foregrounds the urgent need to repeal retrogressive laws such AIPPA.

Because of its undemocratic tenets, the Act has been a subject of heated debate with Government justifying its existence, while civil society and the media have been pushing for its repeal or extensive amendment in line with international best practices.

In spite of its position, over the years the government has taken some steps to effect some amendments to the law on three occasions in 2003, 2004 and in 2007.

However, the effected changes did not deal with much of the substantive matters but mostly with marginal and administrative issues that left the problematic features of the Act intact.

Also, while section 35 criminalised the falsification of personal information belonging to the person in question, the provision was amended in 2003 to extend the liability to persons who falsify personal information about third parties.

Section 37 was also amended to expand the reasons for the disclosure of archived information, such that instead of disclosure for “archival or historical purposes,” such information could be disclosed for the purpose of “historical research or any other lawful purpose.”

Although the 2007 amendments established the Zimbabwe Media Commission to replace the Media and Information Commission, the move simply entrenched a media accountability mechanism rooted in statutory regulation.

This flies in the face of regional and international trends where self-regulation and co-regulation have been adopted as the best models of media regulation.

Section 62 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe provides an explicit guarantee of the right of access to information. In many ways, this is a significant departure from the Lancaster House Constitution.

It also specifically guarantees the right to information when it asserts that: “Every Zimbabwean citizen or permanent resident, including juristic persons and the Zimbabwean media, has the right of access to any information held by the State or by any institution or agency of government at every level, in so far as the information is required in the interests of public accountability”.

It also calls on the government of the day to enact legislation to give effect to this right, but may restrict access to information in the interests of defence, public security or professional confidentiality, to the extent that the restriction is fair, reasonable, necessary and justifiable in a democratic society based on openness, justice, human dignity, equality and freedom.

At the centre of these obligations placed on government and public institutions, is the provision of information relevant to the functions of such institutions and in line with key principles such as proactive disclosure and timely release of information.

The implication of these provisions is that AIPPA or any law in its place must contain measures that promote and facilitate the transparency and accountability envisaged in the Constitution.

In view of the above, it is important for the current government to prioritise the amendment of AIPPA so that it is in sync with the supreme law of the land.

The country can also benefit from drawing on regional benchmarks from countries such as South Africa, Uganda, Kenya and Nigeria, which are some of the African countries that have an access to information regime.

The right of access to information, media freedom, and privacy are all recognised under international and regional legal instruments. These include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [Article 19] and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [Article 19].

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

At a continental level, Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights also entrenches the importance of freedom of expression, access to information, privacy and media freedoms. Zimbabwe is a state party to all these international instruments.

Therefore, any Amendment Bill to AIPPA must take cognizance of the provisions of these instruments particularly those that Zimbabwe is party to, such as of the Declaration of Principles of Freedom of Expression in Africa which is an expansion of Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights.

Besides the obligatory national and international human rights instruments outlined above, the AIPPA amendment bill can also benefit from other non-binding but regionally and internationally recognized instruments and authorities regarding promotion and protection of access to information.

These include: the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, Model Law on Access to Information; the African Platform on Access to Information; International Mechanisms for Promoting Freedom of Expression; the Maputo Declaration Fostering Freedom of Expression, Access to Information and Empowerment of people; the Johannesburg Principles on National Security and Access to Information, 1996; the Atlanta Declaration and Plan of Action for the Advancement of the Right of Access to Information and the Brisbane Declaration: Freedom of Information, The Right to Know.

So what needs to be done?

As already intimated above, there is urgent need to amend AIPPA and ensure that it has sufficient safeguards to protect the collection, disclosure and use of personal information especially in the wake of the biometric voter registration and other national big data projects.

In the age of data deluge, there is also need to ensure that data protection legislation with in-built necessary and proportionate principles is promulgated. This may entail coming up with a standalone Data Protection Bill.

Current measures in AIPPA are inadequate to protect the rights and interests of minors in respect of the collection, disclosure and use of personal information relating to them.

The AIPPA amendment bill must specifically require that in respect of information relating to minors, consent must be obtained first from a minor’s legal, judicial or agreed representative.

Borrowing from section 3(b) of South Africa’s Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA), the Amendment Bill must introduce the right of persons to also access privately-held information in line with the provision of section 62 (2).

The free flow of and access to information including the proactive disclosure of public interest information by information holders are at the centre of public accountability and transparency in public institutions including in public sector finance management.

The Amendment Bill must broaden the scope of the right beyond “records” to include other measures and platforms that provide the public with information as envisaged in section 61 and 62 of the Constitution.

This is because the concept of “Information” is broader than what is stored in a “record” and includes information that is proactively disclosed in the public interest without waiting for information requests.

It also encompasses timely dissemination of public interest information on current issues as they happen, as well as the putting in place of mechanisms to facilitate the dissemination of information through other platforms such as public broadcasting and other online information and technology communication platforms.

In as far as information required for the exercise of rights is concerned, the Amendment Bill must provide for all classes of persons to have access to such information without exclusion as envisaged in section 62(2).

The Amendment Bill must also seek to align existing limitations firstly with the three limitations outlined in section 62(4) i.e. in the interest of defence, public security or professional confidentiality and further in line with the grounds set in section 86 and 87 of the Constitution.

The latter sections provide for the general limitation of all human rights and freedoms as well as their limitation during a public emergency. Further, the Amendment Bill must look to precisely define grounds upon which the right to information may be limited.

Any amendment bill to AIPPA must include a general definition or rider of the “public interest” concept as a way of ensuring that there is clarity on its parameters, thus avoiding the abuse of this concept.

The Amendment Bill must include measures that are wide enough to facilitate the existence of this envisaged environment beyond keeping and providing access to official records.

These could include proactive disclosure obligations for all public institutions, a wider public interest override provision and narrowly couched limitations that will enhance the degree of information such institutions are obliged to release.

The Amendment Bill will need to outline clearly the measures that ought to be taken by public bodies in the collection, use and disposal of personal information by public bodies, for instance, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC).

It must also put in place measures that guard against the abuse or other handling of the information which can detrimental to the person it relates to.

The Amendment Bill will need to include a definition of “media” and distinguish who constitutes the “media” for purposes of accessing information in terms of the law.

There is need for an amended law to establish an independent body that will carry out an oversight function on access to information, as outlined in the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights Model Law and in principle 9 of the African Platform on Access to Information (APAI) Declaration. Equally, the powers and duties of the oversight body must be clearly spelt out.

Aligning of AIPPA remains one of the most important pillars for the realization of a level electoral playing field and the building of strong democratic institutions in post-independent Zimbabwe.

- The writer, Dr. Admire Mare is a Senior Lecturer, Department of Communication at the Namibia University of Science and Technology, Windhoek, Namibia. This article was commissioned by MISA Zimbabwe, as is part of its campaign on the realignment of media laws with the constitution of Zimbabwe.