By Nqaba Matshazi

One thing I have always lamented about journalists and journalism in Zimbabwe is how we have never tested the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA ) to show how it curtails the right to information and curbs freedom of expression and the media.

It is an almost universal truth that AIPPA is a terrible law that hinders freedom of expression. But, there is precious little that has been done to show how bad it is. except, I daresay, for academic purposes and civic society organisations’ position papers.

In an ideal world, a journalist would have approached a government body and sought for information that ordinarily should be in the public domain.

A good example, for me at least, would have been where journalists approached the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) and sought information on the deal between the central bank and Afreximbank on bond notes, whose details have remained hidden from the public.

I can argue that this information is in the public’s interest and Zimbabweans have a right to know the details of the deal, as it has implications on the country’s public debt and has future economic repercussions.

This could have provided an interesting test case for the application of AIPPA, but unfortunately, not much has been done in that regard.

Had, we, as journalists, been brave enough, or at least daring, we would have approached the central bank and after everything else failed, we would have had the leeway to approach the Constitutional Court and this could eventually lead to the repealing of AIPPA, as this has always been the demand by the media and right to information campaigners.

This is a tried and tested method that has worked, as the courts have struck down criminal defamation laws and have outlawed some sections of the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act that outlaw the publication of falsehoods.

There is need for more of this kind of advocacy journalism if I can put it that way, that keeps pushing the boundaries in the hope of enhancing freedom of expression and of the media.

In the absence of that kind of activism, there is a real risk that we will continue bearing the yoke of AIPPA, which everyone knows is past its sell-by date.

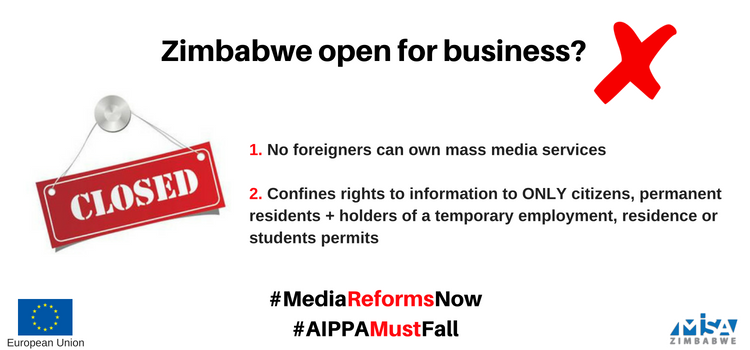

For starters, it is known that AIPPA is misnamed, as its name suggests that it is enabling access to information, when it actually curtails this and helps the government and its arms to conduct their work in a veil of secrecy, with very little in the way of accountability.

For example, AIPPA’s section 5(1) limits access to information held by or under the control of public bodies. This means a patient at a private hospital cannot rely on AIPPA to access information that the hospital may have relating to that patient.

AIPPA states that the promotion of public accountability is only in respect of the correction of misrepresented personal information and not in respect of their operations or the enjoyment of personal rights.

It is clear that the law works not to promote accountability from public bodies, but rather promotes opacity.

AIPPA gives heads of public bodies the right to decide what is in the public interest and what is not and with that discretion, they can block the public from accessing some information.

A basic tenet of democracy is the right to information, where a citizenry makes decisions based on vast amounts of information, rather than this situation where a government official has the discretion to stop people from holding him or her accountable.

Heads of public bodies are given up to 30 days to respond to a request for information and can extend by a further 30 days and still refuse to divulge the information that is sought.

Imagine, as a journalist, having to wait 60 days for information and after that being told that this information is not in the public interest.

There are a few stories with such a shelf life and the head of a public body would have literally killed a story that shines the light in dark spots and holds government bodies to account.

Compare this 60-day period with the 21-day limit provided by Section 15 of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ Model Law on Access to Information and this gives you an idea how constraining AIPPA is.

It is now incumbent for journalists to push the boundaries in their quest for openness by using AIPPA to request for information and if that fails, take it as far as the apex court.

We should not rest on our laurels and complain about how bad AIPPA is without challenging its provisions in court, as the government has shown it clearly has no appetite to repeal the law as it once promised.

- The writer, Nqaba Matshazi is Deputy Editor at The NewsDay. This article was commissioned by MISA Zimbabwe, as is part of its campaign on the realignment of media laws with the constitution of Zimbabwe with support from the European Union.